Table of contents:

- Brain, not bones

- Why are these fables?

- Grunted in annoyance

- We develop the apparatus

- Aperture play

- Silent depths of time

- From proto-proto-language

- What if it's an accident?

- What does the bird want to say?

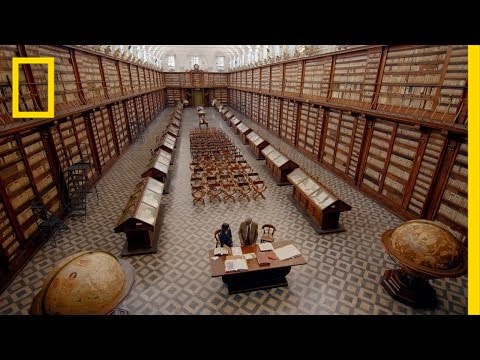

Video: Human language: one of the world's main mysteries

2024 Author: Seth Attwood | [email protected]. Last modified: 2023-12-16 15:55

Language is one of the main features that distinguish a person from the animal world. This is not to say that animals do not know how to communicate with each other. However, such a highly developed, will-driven system of sound communication was formed only in Homo sapiens. How did we become the owners of this unique gift?

The mystery of the origin of language rightfully takes its place among the main mysteries of life: the birth of the Universe, the emergence of life, the emergence of a eukaryotic cell, the acquisition of reason. More recently, it was hypothesized that our species has existed for only some 20,000 years, but new advances in paleoanthropology have shown that this is not the case.

The time of the emergence of Homo sapiens has moved away from us by almost 200,000 years, and the ability to speak, probably, was largely formed by his ancestors.

The origin of the language was not one-step and abrupt. Indeed, in mammals, all children are given birth and raised by mothers, and for the successful rearing of offspring, mothers and cubs - in each generation - must understand each other well enough. Therefore, such a point in time until which the ancestors of a person could not speak, and after which they immediately spoke, of course, does not exist. But even a very slow accumulation of differences between the generation of parents and the generation of descendants over millions (and even hundreds of thousands) of years can result in a transition from quantity to quality.

Brain, not bones

The origin of the language was part of the adaptation of the ancient representatives of our evolutionary line in the direction that is generally characteristic of primates. And it is not the growth of canines, claws or a four-chambered stomach that is characteristic of them, but the development of the brain. A developed brain makes it possible to understand much better what is happening around, find cause-and-effect relationships between the past and the present, and plan the future.

This means choosing a more optimal program of behavior. It is also very important that primates are group animals. In order for them to successfully reproduce their numbers, so that their offspring are not only born, but also live up to some decent age and themselves achieve reproductive success, the efforts of the entire group are needed, a community is needed, permeated with many social ties.

All each other, even if at least unconsciously, should help (or at least not interfere too much). Some elements of cooperation and mutual assistance are quite visible even in modern monkeys. The longer childhood, the more requirements for group cohesion - and therefore for the development of communication tools.

There is a hypothesis according to which the division of the common ancestors of man and modern apes went according to their habitats. The ancestors of gorillas and chimpanzees remained in the tropical jungle, and our ancestors were forced to adapt to life, first in the open forest, and then in the savanna, where seasonal differences are very large and it makes sense for an omnivorous creature to navigate in a huge amount of details of the surrounding reality.

In such a situation, selection begins to favor those groups whose members have a need not only to notice, but also to comment on what they see with the help of certain signals. People have not parted with this passion for commenting to this day.

Why are these fables?

In 1868, the German linguist August Schleicher wrote a short fable "Sheep and Horses" in Proto-Indo-European, that is, a reconstructed language that no one has ever heard. For its time, Schleicher's work might have seemed a triumph of comparative studies, but later, as further developments in the field of Proto-Indo-European reconstruction, the text of the fable was rewritten by linguists more than once.

However, despite the fact that the fable in the language revived "at the tip of the pen" seems to be an amusing illustration (for the uninitiated) of the work of comparativists, such exercises can hardly be taken seriously. The fact is that when restoring the proto-language, it is impossible to take into account that various elements of this reconstruction could belong to different times, and in addition, some features of the proto-language could have time to be lost in all descendant languages.

Not only man is able to react with sounds to some surrounding phenomena: many species of animals have, for example, food cries, cries for different types of danger. But to develop such means, with the help of which it would be possible to comment on anything at all, to hang verbal “labels” on reality in an infinite number (including inventing new ones within the limits of their own lives) - only people have succeeded. It was successful because the groups who had these comments were more pronounced and more detailed turned out to be the winners.

Grunted in annoyance

The transition to sound communication could have started from the time when our ancestors began to regularly make stone tools. After all, while a person makes tools or does something with these tools, he cannot communicate with the help of gestures, like a chimpanzee. In chimpanzees, sounds are not under the control of the will, but gestures are under control, and when they want to communicate something, they enter the “interlocutor's” field of vision and give him a signal with gestures or other actions. But what if your hands are busy?

Initially, none of the ancient hominids thought to "say" something to a relative in this situation. But even if some sound spontaneously escapes from him, there is a high probability that a quick-witted relative simply by intonation will be able to guess what is the problem with his neighbor. In the same way, when a person with different intonations is called his name, he often already perfectly understands what they will turn to - with a reproach, praise or a request.

But he hadn't been told anything yet. If the evolutionary gains go to those groups whose members understand better, selection will encourage ever more subtle differences in the signal - so that there is something to understand. And control over the will will come with time.

We develop the apparatus

In order to better understand (and then pronounce), you need brains. Brain development in hominids can be seen in the so-called endocranes (casts of the inner surface of the skull). The brain becomes more and more (which means that the possibilities of memory increase), in particular, those parts of it are growing where we have "speech zones" (Broca's zone and Wernicke's zone), and also the frontal lobes occupied by higher forms of thinking.

The direct ancestor of man of our species - Homo heidelbergensis - already had a very decent set of adaptations to articulated sounding speech. Apparently, they were already able to manage their audio signals quite well. By the way, paleoanthropologists were very lucky with the Heidelberg man.

In Spain, on the territory of the municipality of Atapuerca, a crevice was discovered where the bodies of ancient hominids were inaccessible to predators, and the remains have come down to us in excellent preservation. Even the auditory ossicles (malleus, anvil and stapes) survived, which made it possible to draw conclusions about the auditory capabilities of our ancestors. It turned out that Heidelberg people could hear better than modern chimpanzees at those frequencies where the signs of sounds that are achieved by articulation work. Different Heidelbergians, of course, heard differently, but in general, an evolutionary line is visible towards a higher adaptability to the perception of sounding speech.

Aperture play

Articulated sounding speech is not easy, because different sounds by their nature have different loudness. That is, if the same sound stream is driven through the oral cavity with different articulations, then the sound "a" will be the loudest, and, for example, "and" - much quieter. But if you put up with this, it turns out that loud sounds of the "a" type will start to drown out other, not so loud sounds in the neighborhood. Therefore, our diaphragm, making amazing subtle movements such as inhalation on exhalation, gently "straightens" our sound flow so that loud sounds are not too loud and quiet ones are not too quiet.

Moreover, air is supplied to the vocal cords in portions, in syllables. And we don't need to breathe in between syllables. We can combine each individual syllable with other syllables, and give these syllables differences - both relative to each other and within the syllable. All this is also done by the diaphragm, but in order for the brain to be able to control this organ so masterfully, a person received a wide spinal canal: the brain needed, as we are now speaking, broadband access in the form of more nerve connections.

In general, with the development of sound communication, the physiological apparatus of speech has significantly improved. People's jaws have decreased - they now protrude not so much, and the larynx, on the contrary, has dropped. As a result of these changes, the length of the oral cavity is approximately equal to the length of the pharynx, respectively, the tongue gains greater mobility both horizontally and vertically. In this way, many different vowels and consonants can be produced.

And, of course, the brain itself received significant development. Indeed, if we have a developed language, then we need to store such a large number of sound forms of words somewhere (and when - much later - written languages appear, then written ones too). Somewhere it is necessary to record a colossal number of programs for generating linguistic texts: after all, we do not speak with the same phrases that we heard in childhood, but we constantly give birth to new ones. The brain must also include an apparatus for generating inferences from the information received. Because if you give out a lot of information to someone who cannot draw conclusions, then why does he need it? And the frontal lobes are responsible for this, especially what is called the prefrontal cortex.

From all of the above, we can conclude that the origin of language was an evolutionarily long process that began long before the appearance of modern humans.

Silent depths of time

Can we imagine today what was the first language in which our distant ancestors spoke, relying on the material of living and dead languages that have left written evidence? If we consider that the history of the language is more than a hundred thousand years old, and the most ancient written monuments are about 5000 years old, it is clear that an excursion to the very roots seems to be an extremely difficult, almost insoluble task.

We still do not know whether the origin of the language was a unique phenomenon or whether different ancient people invented the language several times. And although today many researchers are inclined to believe that all languages we know go back to the same root, it may well turn out that this common ancestor of all dialects of the Earth was only one of several, just the rest turned out to be less fortunate and did not leave descendants that have survived to our days.

People who are poorly versed in what evolution is, often believe that it would be very tempting to find something like "linguistic coelacanth" - a language in which some archaic features of the ancient speech were preserved. However, there is no reason to hope for this: all languages of the world have passed an equally long evolutionary path, have repeatedly changed under the influence of both internal processes and external influences. By the way, coelacanth also evolved …

From proto-proto-language

But at the same time, the movement towards the origins in the mainstream of comparative historical linguistics is going on. We see this progress thanks to the methods of reconstruction of languages from which not a single written word remains. Now no one doubts the existence of the Indo-European family of languages, which includes the Slavic, Germanic, Romance, Indo-Iranian and some other living and extinct branches of languages that originated from one root.

The Proto-Indo-European language existed about 6-7 thousand years ago, but linguists managed to reconstruct its lexical composition and grammar to a certain extent. 6000 years is a time comparable to the existence of civilization, but it is very small in comparison with the history of human speech.

Can we move on? Yes, it is possible, and quite convincing attempts to recreate even earlier languages are being undertaken by comparativists from different countries, especially Russia, where there is a scientific tradition of reconstructing the so-called Nostratic proto-language.

In addition to Indo-European, the Nostratic macrofamily also includes the Uralic, Altai, Dravidian, Kartvelian (and possibly some more) languages. The proto-language from which all these language families originated could have existed about 14,000 years ago. The Sino-Tibetan languages (which include Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese and other languages), most of the languages of the Caucasus, the languages of the Indians of both Americas, etc. remain outside the Nostratic macrofamily.

If we proceed from the postulate of a single root of all languages of the world, then it seems possible to reconstruct the proto-languages of other macrofamilies (in particular, the Sino-Caucasian macrofamily) and, in comparison with the material of Nostratic reconstruction, go further and further into the depths of time. Further research will be able to significantly bring us closer to the origins of the human language.

What if it's an accident?

The only question that remains is to verify the results obtained. Are all these reconstructions too hypothetical? After all, we are already talking about a scale of more than ten thousand years, and the languages underlying macrofamilies are trying to learn not on the basis of known languages, but on the basis of others, also reconstructed.

To this we can answer that the verification toolkit exists, and although in linguistics, of course, the debate about the accuracy of this or that reconstruction will never subside, comparativists may well present convincing arguments in favor of their point of view. The main evidence of the kinship of languages is regular sound correspondences in the most stable (so-called basic) vocabulary. When looking at a closely related language such as Ukrainian or Polish, such correspondences can be easily seen even by a non-specialist, and even not only in the basic vocabulary.

The relationship between Russian and English, belonging to the branches of the Indo-European tree, which split about 6000 years ago, is no longer obvious and requires scientific justification: those words that sound similar are likely to turn out to be coincidences or borrowings. But if you look more closely, you can see, for example, that English th in Russian always corresponds to "t": mother - mother, brother - brother, outdated thou - you …

What does the bird want to say?

The development of human speech would be impossible without a number of psychological prerequisites. For example, a person really wants to hear understandable speech. As a result, he is able to hear it in anything. The lentil bird whistles, and the person hears "Did you see Vitya?" A quail in the field is calling "Pod weed!"

The child hears the stream of words uttered by the mother, and, not yet knowing what they mean, nevertheless already understands that this noise is fundamentally different from the noise of rain or rustling of leaves. And the baby responds to his mother with some kind of stream of sounds, the one that he is currently capable of producing. That is why children easily learn their native language - they do not need to be trained, rewarding for every correct word. The child wants to communicate - and quite quickly learns that the mother responds to an abstract "vya" worse than to anything more like a word.

In addition, the person really wants to understand what the other meant. You want so much that even if the interlocutor made a slip of the tongue, the person will still understand him. A person is characterized by cooperativeness in relationships with other people, and as far as the communication system is concerned, it is brought to a subconscious level: we adapt to the interlocutor completely unconsciously.

If the interlocutor calls an object, say, not a "pen", but a "holder", we will most likely repeat this term after him when we talk about the same subject. This effect could be observed in the days when SMS was still in Latin. If a person received a letter where, for example, the sound "sh" was transmitted not by the combination of Latin letters to which he was accustomed (for example, sh), but in a different way ("6", "W"), then in the answer this sound was most likely encoded just like the interlocutor. Such deep mechanisms are firmly embedded in our today's speech habits, we do not even notice them.

Russian and Japanese seem to have nothing in common. Who can think that the Russian verb "to be" and the Japanese verb "iru" ("to be" as applied to a living being) are related words? However, in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European for the meaning of "to be" is, in particular, the root "bhuu-" (with a long "u"), and in Proto-Altai (the ancestor of the Turkic, Mongolian, Tungus-Manchurian, as well as Korean and Japanese languages) the same meaning is assigned to the root "bui".

These two roots are already very similar (especially if we consider that the Altaic voiced ones always correspond to the Proto-Indo-European voiced aspirates, and combinations of the "ui" type were impossible in the Proto-Indo-European). Thus, we see that over the millennia of separate development, words with the same root have changed beyond recognition. Therefore, as evidence of a possible kinship of distantly related languages, comparativists are looking not for literal matches (they are just likely to indicate borrowing, not kinship), but persistently repeating sound matches at roots with a similar meaning.

For example, if in one language the sound "t" always corresponds to the sound "k", and "x" always corresponds to "c", then this is a serious argument in favor of the fact that we are dealing with related languages and that on their basis we can try to reconstruct ancestor language. And it is not modern languages that need to be compared, but well-reconstructed proto-languages - they have had less time to change.

The only thing that can be used as a counterargument against the hypothesis of the kinship of these languages is the assumption of the random nature of the identified parallels. However, there are mathematical methods for assessing this probability, and with the accumulation of sufficient material, the hypothesis of the accidental appearance of parallels can be easily rejected.

Thus, along with astrophysics, which studies the radiation that has come to us almost since the Big Bang, linguistics is also gradually learning to look into the distant past of the human language, which has left no trace either on clay tablets or in the memory of mankind.

Recommended:

25 main mysteries of Russian pre-Petrine history

Churchill complained that he could not predict the actions of Russia, since "Russia is a riddle wrapped in mystery, placed inside a puzzle." This quote from a British politician would be the best epigraph for a textbook on Russian history. We present our version of the 25 main mysteries of the Russian history of the pre-Petrine time

Coat of arms: The history of one of the main symbols of Russia

The history of the coat of arms of Russia dates back to the end of the 15th century, during the reign of Ivan III, when for the first time the image of a two-headed eagle appeared on the seal of the sovereign. It was this emblem that became the main element of the coat of arms, which has undergone various changes over time

How did the human language of TOP-6 theories appear?

The question of the origin of language has occupied many prominent thinkers, but it was posed and resolved in very different ways. So for the famous scientist Potebnya, this was a question "about the phenomena of mental life that preceded language, about the laws of its formation and development, about its influence on subsequent mental activity, that is, a purely psychological question."

Russian language under the yoke of English-language verbiage

Those who travel a lot to English-speaking countries know well how zealously they guard their language

Why Novgorod letters are one of the main discoveries of the twentieth century

Everyone has heard about birch bark letters, but they know much less about the extent to which they have changed our ideas about Russian history. But thanks to the letters, scientists were not only able to imagine in detail the economic life of the ancient city, but also learned how Novgorodians spoke, and at the same time found out that literacy was not only the lot of the social upper classes, as it seemed before, but was widespread among the townspeople